Across the globe, the people who run our elections are being undermined, targeted, and attacked. Here is how to shore them up—and protect democratic institutions, too.

October 2022

By Fernanda Buril and Erica Shein

Elections don’t run themselves. How an election is conducted—from the registration of voters and candidates to the tallying and final certification of the results—determines whether it’s a free and fair contest or a rigged and undemocratic one. In most democracies, elections are administered by professional, politically independent institutions, or so-called election management bodies. Election management usually garners little public attention before polling day, particularly in countries where the rules of the democratic game are widely accepted.

In recent years, however, election administration has increasingly come under fire, even in places where democracy was thought to be most firmly entrenched. Aggrieved candidates and elected incumbents alike are discrediting election results before and after they are released. But the most dangerous efforts to undermine the fair administration of elections arguably happen out of the public eye. Once in office, leaders are employing subtle tactics to coopt or weaken election management, jeopardizing electoral fairness, public trust, and democracy itself.

Elections Under Attack

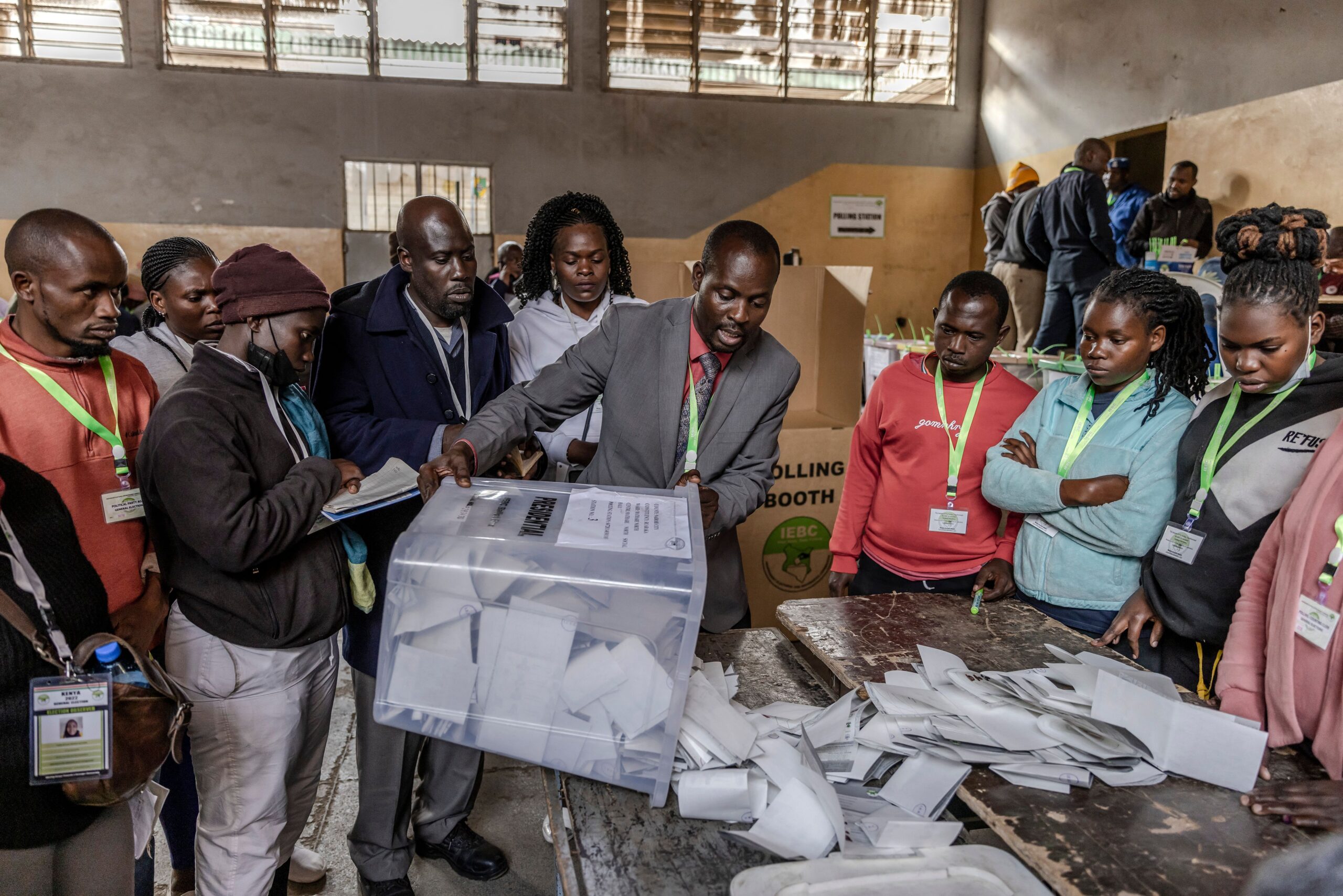

Rhetorical attacks against the electoral process are fostering public distrust in democracy and leading to violence. A Reuters investigation of violence against U.S. election officials and their families in eight battleground states identified 102 threats of violence, all of which seemed to have been motivated by former president Donald Trump’s spurious allegations that the 2020 election was rigged. After losing the 2014 Indonesian presidential race, Prabowo Subianto claimed “massive fraud” and rejected the results. His allegations sparked protests, where some of his supporters reportedly were arrested and injured. After Kenya’s presidential election in August 2022, allies of defeated presidential candidate Raila Odinga claimed fraud and stormed the national vote-tallying center, injuring election officials in the process.

Nevertheless, democracy appears to have prevailed in the United States, Indonesia, and Kenya—in these elections, at least. While Trump continues to publicly question his loss, and doubt about the results is widespread among his supporters, the U.S. courts overwhelmingly rejected the Trump campaign’s allegations, corroborating the results from election officials nationwide. In Indonesia, the General Elections Commission proactively released image scans of the vote tallies from the more than 500,000 polling stations in order to encourage public confidence in the official results. Once the Supreme Court ruled that Prabowo failed to produce evidence supporting his election-fraud claims, he conceded the race. Kenya’s Supreme Court issued a unanimous judgment confirming the certified election results, and Odinga accepted them.

These cases show that election officials can be a bulwark for democracy by providing independent and accurate vote tallies even while under significant political pressure. To do so, they need to be adequately resourced and strictly independent from politics. That shouldn’t be taken for granted.

Reining in the Refs

Varieties of Democracy’s 2022 Democracy Report shows that government authorities are increasingly attempting to undermine independent election administration in their countries. In the last decade alone, 25 countries saw the independence of their election administration decrease. By exerting political influence on election officials, government authorities can transform once effective and independent institutions into rubber stamps for their power grabs.

Venezuela is a perfect example. The country was once considered to have very sophisticated, high-performing election technology and voting procedures, but as the ruling party packed the National Electoral Council with loyalists, credible results could no longer be expected. In 2017, Smartmatic, a software company that was supporting Venezuela’s election systems, stated that the vote count from that year’s legislative elections had been manipulated by at least a million votes “without any doubt”—an extraordinary public statement by a private vendor.

Election-management bodies are under pressure across the globe. In April 2022, the U.K. Parliament passed a law that could give ministers greater say in the operations of the Electoral Commission. Watchdog organizations, opposition parties, and even the Electoral Commission itself warned that the law could undermine the integrity of election administration. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador continues to push legal reforms that experts argue would enable political parties to select friendly commissioners to lead the National Electoral Institute and undermine its autonomy.

Some leaders are taking more circuitous paths to controlling the administration of elections: Rather than attack election-management bodies directly, leaders target the institutions with authority over them. In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele and his allies in the legislature ousted all the top judges on the country’s highest court and appointed new ones, including a former presidential assistant. A few months later, the court issued a reinterpretation of the constitution that should allow Bukele to run for reelection in 2024. El Salvador’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has no option but to accept and implement the court’s decision. Since taking office in 2016, Benin’s President, Patrice Talon, with the support of allies on the country’s top court, has pushed excessive candidate- and party-registration laws designed to narrow the electoral playing field. When the Autonomous National Electoral Commission enforced the new laws, it disqualified all opposition parties in the 2019 parliamentary races, all but one opposition party in the 2020 local races, and 17 of the 20 candidates in the 2020 presidential race. The Commission has also seen its budget manipulated by the Ministry of Finance, further reducing its ability to effectively administer elections.

When attacks on elections are surreptitious or indirect, it is difficult for democracy’s champions to fight back. These efforts—including suspicious appointments, laws, or budget cuts—can be relatively slow and bureaucratic. They usually do not capture media attention or trigger public outrage. Little by little, elected leaders can coopt the electoral referees.

Accountability Is the Answer

To defend democracy’s most critical process, election-management bodies need to be strong, resilient, and independent. The best way to keep election administration fair is to subject it to public scrutiny through transparency and accountability. Institutions charged with running elections should be required to publicly explain their spending and decisions regarding campaign regulations and voting procedures. Election-management bodies can establish their own reporting mechanisms and protections to enable staff members to report wrongdoing without fear of retaliation. Comprehensive training can further increase election administrators’ ability to prevent, identify, and address corrupt practices and misconduct.

Election officials can also collaborate with likeminded actors to further bolster the credibility and integrity of the voting process. Government oversight bodies can provide additional layers of independent scrutiny. Technical assistance from experts can help to address any gaps in the election process that could be exploited by malicious actors. Independent international observers can help to increase the credibility of election results by issuing neutral, objective reports on the soundness of voting procedures. And the public should be engaged in the election-administration process through wide-ranging consultations and outreach.

The value of accountability mechanisms is multifold; in addition to holding election administrators to account, outreach and transparency efforts give administrators the opportunity to build public awareness of their mandates, to show how they are using public resources and why they need them, and—most crucially—to garner the popular legitimacy needed to weather attacks on their independence.

Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has taken preemptive measures to dispel doubts in the results of the 2022 presidential election. It has permitted political parties and government bodies to inspect voting machines and invited international experts to observe the election process. President Jair Bolsonaro invited foreign diplomats to the presidential palace to air his doubts about the electronic voting system and accusations that Supreme Court judges were trying to sabotage his reelection bid. Election officials in turn held events engaging diplomats, civil society and religious leaders, and social-media influencers. It is not yet clear what long-term impact Bolsonaro’s attacks on the election process will have on Brazilians’ trust in democracy. As the United States’ experience has shown, democracy might survive—but not unscathed. Doubt and unfounded allegations of fraud may persist despite largely transparent and credible election administration.

Election administrators are even more likely to lose battles that are fought behind the scenes, away from public and media attention. While public attacks and accusations of fraud can undermine voter trust, strong election-management bodies have the means—however imperfect—to respond. Equipped with facts and evidence of clean elections, they are more likely to maintain domestic and international support. But when antidemocratic leaders succeed at eroding election officials’ independence and capacity, they also deplete these officials’ will and ability to fight back.

The global decline in independent election management is a clear sign that antidemocratic leaders may be winning. Their tactics for undermining the vote vary from subtle tweaks to the appointment process for election administrators to brash disinformation campaigns. Shoring up the resilience of election management requires constant vigilance from administrators and the public alike. Accountability is essential to building public trust and preventing irreversible damage to this cornerstone of democracy.![]()

Fernanda Buril is deputy director of the Center for Applied Research and Learning at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES). She is the lead author of Overcoming Challenges to Democracy and Governance Programs in Post-Conflict Countries (2021). Erica Shein is managing director of the IFES Center for Applied Research and Learning. She is the coauthor of Risk-Limiting Audits: A Guide for Global Use (2021).

Copyright © 2022 National Endowment for Democracy

Image Credit: Luis Tato/AFP via Getty Images