The South American country was once the most coup-prone in the world. Many thought it had closed that chapter. So why did it just suffer another attempted coup?

By John Chin and Joseph Wright

June 2024

On June 26, Bolivian general Juan José Zúñiga launched what appeared to be a coup attempt against President Luis Arce. Troops loyal to the general, who had been Bolivia’s top army commander until the day before, occupied Plaza Murillo — La Paz’s main square, lined by the presidential palace, national congress, and cathedral — and tried to storm the presidential palace. Within hours, the coup had failed and Zúñiga was arrested.

The reason behind the attempted coup remains contested. Zúñiga told reporters that he was acting on the president’s orders, alleging that Arce had arranged the plot so that he could portray himself as a champion of democracy. With Arce desperate to gain advantage over his rival, former president Evo Morales, ahead of the 2025 presidential election, political analysts say it is possible that this actually was an undercover autogolpe (self-coup). Whatever the cause, recent events have shown that in Bolivia, the military coup may have been beaten down, but it is not dead.

Here’s what you need to know.

Why Bolivia’s Coup Attempt Came as a Surprise

Bolivia’s latest attempted coup runs counter to recent trends. In the last four years, there were no military coup attempts in Latin America. According to the Colpus dataset on military and nonmilitary coup attempts, there have been nine successful coups and five failed coup attempts worldwide since 2020. With the exception of the military takeover in Myanmar in February 2021, all were in Africa.

In contrast to the Cold War, when Latin America was one of the most coup-prone regions, a noted coup scholar declared coups “almost extinct” in Latin America in 2016. Many still assume that “today’s generals don’t want to replace civilian governments” in the Americas, and that the advent of competitive electoral politics has helped the region “break out of the coup trap.”

Such triumphalism over coups might be premature. Coups may have become less common in Latin America, but they are not yet extinct. Take Bolivia, for example: For much of the Cold War, Bolivia was the most coup-prone country in the world, with 28 coup attempts between 1946 and its democratic transition in 1982. During this period, Bolivia was ruled by seven distinct dictatorships and 24 different leaders, eleven of whom were ousted in coups. After 1984, however, Bolivia experienced no coup attempts until November 2019.

What Happened in 2019

Evo Morales won the first round of the 2019 presidential election by 10 percentage points, but in the wake of protest violence, he agreed to a new vote. Yet the military forced him to resign, and Morales fled to exile in Mexico. Spurious allegations of election fraud, supported by the Organization of American States and international media, including the New York Times, prompted widespread protests, cementing the military’s resolve to intervene. (The Times later admitted its mistake.)

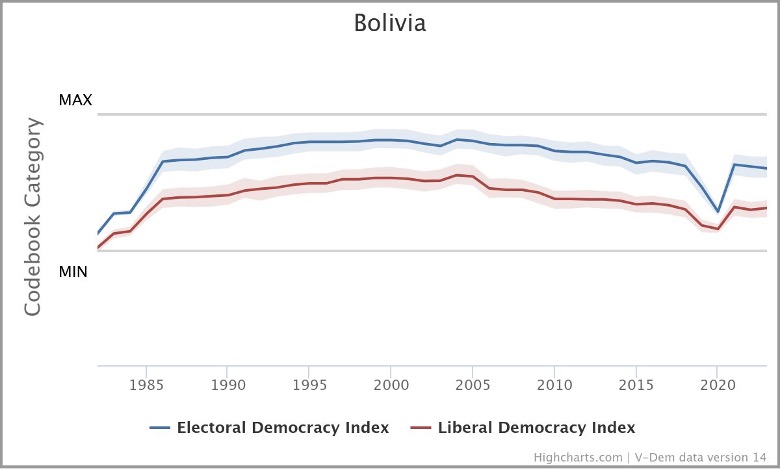

After a brief authoritarian interlude in which an opposition politician, Senator Jeanine Añez Chavez, declared herself president, free and fair multiparty elections were held in October 2020. Luis Arce, the candidate of Morales’s Movement Toward Socialism (MAS), won that vote. Although Arce, who had served as Morales’s finance minister and economy minister, and Morales are feuding for control of the MAS, democracy levels rebounded quickly after 2020 to pre–2019 coup levels.

The 2019 coup followed mass protests and was arguably a response to gradual democratic backsliding — or autocratization — under Morales, whose increasingly personalist rule culminated in a successful bid to end presidential term limits so that he could run again in 2019. But since 2021, Bolivia has rebounded with a post-coup democratic transition.

Yet we know that fledgling democracies, such as Bolivia, face higher coup risks than more entrenched ones. Bolivia also suffers from high political and social polarization, and has been struggling through one of its worst economic recessions in decades — conditions that also might precipitate a putsch. Bolivia thus remains structurally at risk of coups and democratic reversal. Furthermore, observers fear that the growing rift within the MAS between Arce and Morales, who declared his intention to run for president again next year, could spark renewed political violence.

The day before Zúñiga launched his failed coup, Arce had sacked him for threatening to block Morales from running in the next election. The attempt to overthrow Arce thus appears to have been in retaliation for having fired the army commander over interfering in electoral politics.

Why did Zúñiga’s Coup Attempt Fail?

Like most failed coups, Zúñiga’s attempt to storm the presidential palace fell flat because he lacked support from other senior military officers. During a typical coup attempt, most of the military sits on the fence, waiting to see who will come out on top — the president or the coup leader. For this reason, perceived momentum and consensus shape how the military rank and file respond.

This is how civilians can either abet a coup or help to stop it. When protesters demand that the president step down and civilian opposition leaders seem keen to unconstitutionally assume power, military putsches are more likely to succeed. But when supporters of the ousted president mobilize civil resistance, they can defeat coups d’état.

This is what happened in Bolivia: As the presidential palace was surrounded by Zúñiga’s forces, President Arce remained defiant and rallied his supporters. “The Bolivian people are summoned today. We need the Bolivian people to organize and mobilize against the coup d’état in favor of democracy,” Arce said. Evo Morales likewise rallied his own supporters to take to the streets and demand that the attempted coup be stopped.

Arce quickly named a new army commander, who ordered the mutinous troops to stand down. Condemnations of the coup poured in from the international community. Faced only with opposition, Zúñiga’s troops withdrew, allowing hundreds of Arce’s supporters to rush Plaza Murillo, waving Bolivian flags and singing the national anthem in celebration.

Civil society mobilization has increased in recent decades. Indeed, popular protests forced two Bolivian presidents to resign before the end of their terms — Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (2002–2003) and Carlos Mesa (2003–2005). Mobilization of civil society also helped democracy in Bolivia in 2020, when the unelected president twice delayed promised elections. According to new Colpus mass mobilization data, there has been anti-coup mass mobilization during or immediately following nine coup attempts in Bolivia since 1946, with labor unions and university students often playing a key role in stopping takeovers attempts.

How Will the Coup Attempt Affect Bolivian Democracy?

It’s too early to tell. Much will depend on how Arce and other political actors respond to the crisis, how the investigation is conducted, and whether and how the coup leaders are punished. On the one hand, the failed coup could strengthen public (and military) support for anti-coup norms, which some observers feared had been weakening in recent years. On the other hand, failed coups often lead to personalization, which is a bad omen for democracy in the long run.

For now, Bolivia’s political future remains to be written. But the events of this week are an urgent reminder that it’s still difficult for many countries to break out of the coup trap for good.![]()

John Chin is assistant teaching professor of political science in the Carnegie Mellon Institute for Strategy and Technology at Carnegie Mellon University. Joseph Wright is a professor of political science at Pennsylvania State University. They are the authors (with David Carter) of the Historical Dictionary of Modern Coups D’état (2022).

Copyright © 2024 National Endowment for Democracy

Image credit: Gaston Brito Miserocchi via Getty Images

|

FURTHER READING |

||

Why Militaries Support Presidential CoupsIf you want to understand why generals support a presidential power grab, then you need to understand the logic that motivates them. Why they leave the barracks — and what we must do to get them to stand down. |

Standing Up to Africa’s JuntasJoseph Siegle and Jeffrey Smith |

The Myth of the Coup ContagionMany fear that coups are making a comeback. While this is not true, one thing is alarming: Anti-coup norms are starting to erode. |